Targeted Therapy in Advanced and Metastatic Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer. An Update on Treatment of the Most Important Actionable Oncogenic Driver Alterations.

An updated review of the most current targeted therapies in NSCLC (non-small cell lung cancer) by targetable mutation.

Dr. David Konig, Dr. Spasenija S. Prince, and Dr. Sacha I Rothschild did a great review on the current status of targeted therapy in NSCLC (non-small cell lung cancer). Because of the advancement of molecular diagnostics and targetable oncogenic drivers, there are more therapeutic options available to patients compared to even 10 years ago.

Lung cancer is by far the leading cause of cancer-related mortality worldwide, accounting for about 20% of all cancer deaths in Europe. Most of lung cancer is NSCLC at 85% comprised of adenocarcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, and large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. Because of the advances of molecular diagnostics, the sub-typing of various cancers is moving toward a molecular level and is not solely based on the morphological classification of location/cell type.

Most oncogene-driven cancers share similar characteristics:

Often oncogene drivers are mutually exclusive. If you have one, you usually do not have another active driver.

Using targeted therapy is often superior to conventional chemotherapy.

By properly selecting the correct TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor), one can dramatically increase the response rate (50-90%).

Response to TKIs is usually observed within 4-6 weeks of treatment.

Emergence of secondary resistance is inevitable and usually occurs as early as 12-24 months of starting treatment (this number varies for different targets). Further molecular re-analysis at the time of progression opens up more therapeutic options.

Right now, the focus is on ensuring doctors can find out about the morphological subtype (NSCLC for example), PD-L1 status and any targetable oncogenic drivers for patients with advanced, inoperable lung cancer. Current genes to test for are EGFR, ALK, ROS1 and BRAF. Though with an exponential increase in knowledge, other genes such as MET, RET, NTRK, KRAS and HER2 will probably soon be included on the list. Right now, only non-squamous cell carcinoma of the lung is not getting tested for oncogenic drivers, except for patients with never-/light-smoking history or of a younger age.

Researchers have been improving on the techniques used to detect various genetic alterations. The standard is tissue biopsy. DNA- and RNA-based next generation sequencing (NGS) is being used more frequently. Regardless of which method is used, there is always some error involved. For example, in a cohort of 232 adenocarcinoma patients tested by NGS, about 27 actionable gene fusions were missed (11.5% error) and 6 MET exon skip mutations were not found (2.5% missed). Even very standard tests like immunohistochemistry (IHC) in ALK and ROS1 patients can have variable results. IHC test results in ROS1 patients should always be confirmed by a molecular method. Besides being more cumbersome to use as a detection method, IHC has other limitations such as obtaining tissue sample or no established antibody for IHC testing (in the case of RET). In the case of MET amplification, using IHC may be too arbitrary for technicians to detect the level of increase observed, which makes it challenging for positive results to be considered definitive.

Using liquid biopsy can be a preferred method. Many tumors in the body shed ctDNA (circulating tumor DNA) into the blood, providing a whole-body view instead of just from one spot (tissue biopsy). Additionally, this method is less invasive to the patient - a blood draw vs. a procedure. Liquid biopsy can be used multiple times as a tool to sequentially analyze the progress of the patient.

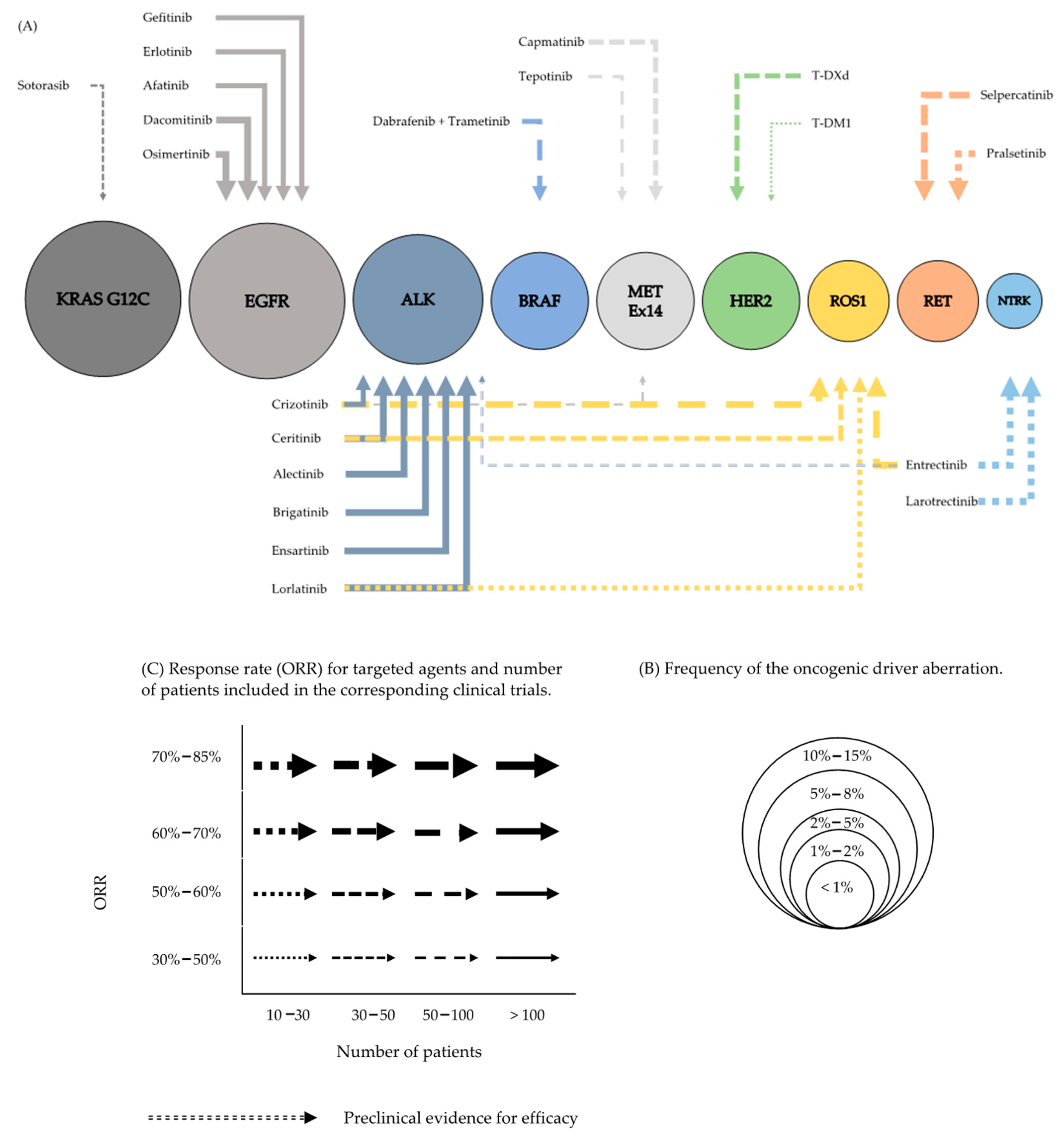

A graphic representation of the frequency of mutations and their target was illustrated by the authors. The bigger the circle, the more frequently those mutations are found. The arrow indicates the response rates seen in studies.

A table summarizing various drugs being used for each genomic driver (edited version).

The authors go into detail on each drug being studied. In addition, the authors highlight other less known drugs used to target these mutations. For example, they listed Rociletinib, Abivertinib,L Lazertinib, Nazaritinib and Alomneritinib as 3rd generation EGFR inhibitors.

ALK is a tyrosine kinase receptor that is expressed in neural tissue, the small intestine and the testes and is implicated to play a crucial role in central nervous development. The aberrant ALK, by fusion with various partners, leads to an upregulation of downstream signaling pathways such as PI3K/mTOR and RAS/RAF/MAPK cascade. Durable responses are not often observed with Crizotinib because the median progression free survival is about 7-10.9 months.

All TKIs used in ALK have been compared with Crizotinb and other TKIs tend to have less toxicity, longer durability and specificity to ALK, except for Ensartinib. There were more adverse events on a head-to-head comparison of Ensartinib vs. Crizotinib, but the overall response rate was longer on Ensartinib.

Studies on Entrectinib on ALK are still pending. This inhibitor is currently under study against Crizotinib on a head-to-head trial (NCT02767804).

This paper highlights the direction of cancer research on oncogenic drivers. Much research is still ongoing and scientists are still researching the many pieces of this field.

This paper was published in February 2021.

https://www.mdpi.com/2072-6694/13/4/804/htm

Author: Alice Chou